We hope to see you again soon!

You are now leaving Lundbeck UK's website (www.lundbeck.com/uk) for an external website. External links are provided as a resource to the viewer. Lundbeck UK are not responsible for the external website and its content.

UK-NOTPR-1010 | April 2022

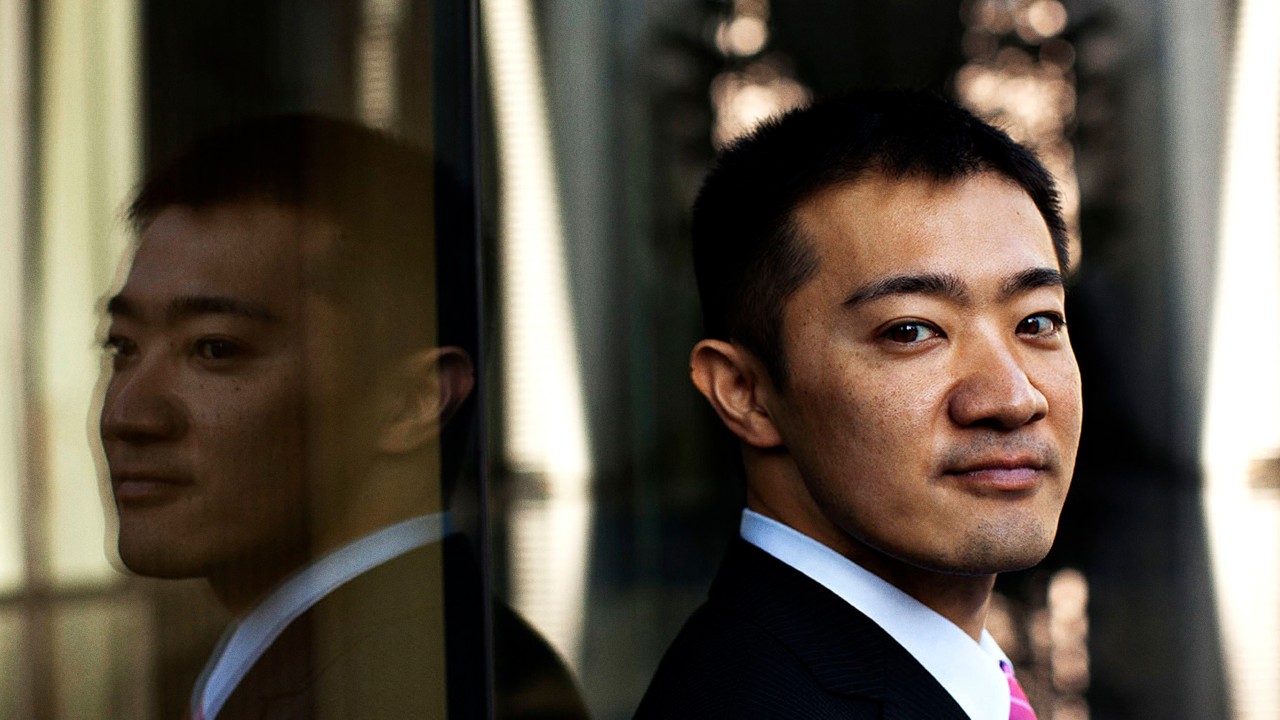

Masashi Fujisawa

I could see, I could think, but I couldn’t move at all

Masashi Fujisawa longed to stand out. But anxiety forced him to withdraw.

Masashi Fujisawa

Japan

35 years old, lives with parents and two siblings

Employment

Employed full time in an organisation that helps people living with physical and mental disabilities to find work.

Diagnosis

General anxiety disorder (GAD). Masashi has not experienced heart palpitations or sweats in many years.

The passengers in the Tokyo metro sit lost in thought. There’s no reason they should notice Masashi, but that could change at any moment. The mere thought gives the slender 21-year-old student the urge to crouch beneath his seat, hands over his head for protection.

He’s heading home from his classes in hotel administration. Masashi has already had the good fortune to secure a job as bellboy at one of Tokyo’s finest hotels. In his spare time he loves to go to wrestling matches and later stand next to the muscular wrestlers to have his picture taken. But right now his heart is racing faster and faster; surely it will burst. Masashi tries to keep still. His face glistens with sweat.

If he dies now, everyone’s eyes will be on him.

A body goes haywire

Today, Masashi is 35. When he recounts his life, it seems like a low-voltage buzz of dread has been with him ever since he was a child. Back then, it was the fear that his father would raise his voice in anger, that strong boys would wrestle him to the ground, that the teacher would rap his knuckles against Masashi’s head. It was impossible to defend himself against so many humiliations. He withdrew so far into himself, that though he yearned to come out of hiding, he often found he couldn’t. “I really wanted to try out for the important positions on my baseball team, but I couldn’t speak up for myself.”

Still, as a young man Masashi stood out as a high achiever. But that day in the metro wasn’t the first time his body had, suddenly and inexplicably, gone haywire. “My life was firmly on track. But I had been experiencing tremors and sweats more and more, though they weren’t as frightening as that day in the metro. And at night my body would freeze up – I could see, I could think, but I couldn’t move at all.”

Masashi was intensely reluctant to make a fuss. But that day in the metro, he got off at the next station and asked a police officer to call an ambulance. At the hospital, the doctor gave him some news about his heart that came as no relief at all. There isn’t any danger, the doctor said. Nothing wrong with your heart. Just go home.

His words made Masashi totally frantic – on the inside.

“I couldn’t ask them for support. How could I confess my weakness? They all knew me as a success. Shame on me for being miserable!”

Masashi Fujisawa

Shame on me

A short time later, he received an anxiety diagnosis. But that didn’t stop the anxiety from invading his life. It taught him to dread the metro, and the mere thought of landing in an ambulance again would trigger a panic attack. Soon, Masashi didn’t dare to leave home – and reaching out to his friends was out of the question. “I couldn’t ask them for support. How could I confess my weakness? They all knew me as a success. Shame on me for being miserable!” Instead, he gave up the two most important things in his life: his schooling and his job.

It wasn’t only Masashi who was unable to express what was happening to him. As he remembers it, a profound silence descended on his entire family. Most of the time, he would hide inside his room. “I read self-help books in there. Books on how to become successful. I only came out for meals and baths.”

In the years that followed, Masashi sought to adapt to his anxiety so that he could live in its shadow. He managed to hold on to various part-time jobs, including newspaper delivery, and he began treatment at a psychiatric clinic. Yet his anxiety persisted. Masashi slid further and further away from the goals that had seemed so attainable just a few years previous. And his family let him know it. “My father would grumble, ‘Why don’t you get a better job?’ My feeling was, I’m doing my best. I have some kind of job! But I wouldn’t say anything.”

Four years after the incident in the metro, the disease had taken full control. He quit his small jobs, lived at home and went on disability. His life limped along. Then one afternoon, he was sitting and surfing TV channels when he heard something that made him prick up his ears.

He’s describing me

An adolescent psychiatrist was talking. He spoke of the reasons that young people became anxious. He spoke of how to support them in becoming more mature and independent. This psychiatrist specialised in social withdrawal. When Masashi recalls his immediate reaction to the specialist’s words, his voice rises: “I felt, That’s me! He’s describing me!”

The experience spurred Masashi to action, and soon after, he found himself – and his father – sitting in the consulting room of the very same psychiatrist.

The father set about describing how disappointed he was in his son. “My father said, ‘I’m getting tired of him.’ And he said that if the psychiatrist were to recommend institutionalised care that would be just fine.” Masashi listened in silence. But then he heard something astonishing: someone opposing his father. For the psychiatrist replied that no – Masashi shouldn’t be sent away. On the contrary, he should be treated in his home, and his family would play a central role in his recovery.

Masashi could feel his father stiffen. But he also felt another sensation surging through his own body. “It was a rare moment. I felt so comforted. The psychiatrist was on my side!”

“It was a rare moment. I felt so comforted. The psychiatrist was on my side!”

Masashi fujisawa

Reclaiming his life

Masashi was 25 at the time and completely cowed by fear. It was a powerful tyrant that he would have to reclaim his life from. The psychiatrist set his new patient many demanding tasks so that he would succeed – and also involved the family. He asked Masashi’s father to sign a contract in which he promised not to yell at his son, and to listen to him without interrupting. Masashi’s father signed. Today Masashi says with a smile that, while his father certainly hasn’t always lived up to the contract’s terms, nothing is as it was before.

Some years after that first consultation, Masashi was ready to be eased into a workplace that accommodated vulnerable employees. In the beginning, he worked three hours a day. He also started taking psychology classes at correspondent university. In them, he’s been learning to understand not only himself, but also the people who it’s become his job to help – for Masashi was hired by an organisation that assists people who have physical and mental disabilities. “My job is to support our clients in finding work. I can use my psychological knowledge to coach them in solving their problems.”

“My life has changed slowly,” he adds. Yet the changes have been substantial: now he can work full time and he has just taken the last exams for his degree. He’s even able to ride the metro again.

That doesn’t mean that he’ll never feel vulnerable again. Masashi’s newly won resilience is tested frequently. He says that recently, for instance, his manager called him into his office. The manager’s booming voice often makes Masashi start. “What springs to mind is: What did I do wrong? But I try to follow the instructions on how to deal with my fears: I delay my response. I monitor myself. And I remind myself that as a last resort, I can ask my psychiatrist to intervene on my behalf.”

Just the thought of being under his psychiatrist’s protection was enough. The inner trembling that warns of approaching anxiety started to subside. His body told him that he was calm.

Then he walked into his manager’s office.

More stories from Lundbeck

UK-NOTPR-2181 | October 2024